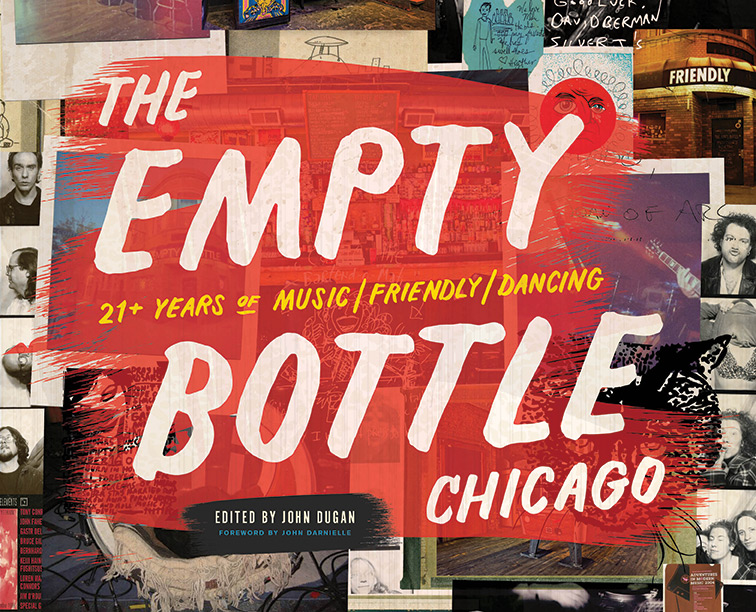

The Empty Bottle Chicago: 21+ Years of Music / Friendly / Dancing

I edited a book on Chicago's Empty Bottle. The book comes out in a few weeks. Editing, in this case, was largely concerned with gathering material--essays, interviews, photos, poster images. Preview coverage for the book is in the links below.

Get it while it's hot: Order The Empty Bottle Chicago: 21+ Years of Music / Friendly / Dancing from Amazon.

An oral history of the Empty Bottle, Chicago Reader

THAT TIME JAY REATARD RIPPED DOWN A DISCO BALL AND MORE: A SELECT HISTORY OF CHICAGO'S EMPTY BOTTLE, Noisey

What Do You Wear When You’re a ’90s Rock Band?, NY Mag The Cut

Empty Bottle Book Revisits 21-Plus Years of Underground Chicago Music, Chicago Tonight WTTW

New book takes a trip down memory lane at the Empty Bottle, Chicago Sun-Times

Travel back in time with photos from the Empty Bottle book, Time Out Chicago

JOHN DARNIELLE ON BELOVED CHICAGO MUSIC VENUE, THE EMPTY BOTTLE, LitHub

Here's an unpublished interview I did re: the book.

The book was originally subtitled "Twenty-plus Years of Piss, Shit, and Broken Urinals"? What was behind the change? (The new one's just a little sunnier?)

The project itself as well as that working title were in place before I came on board. I never felt invested in that subtitle and as the project took shape, I realized it didn't have much to do with how I think about the Empty Bottle and played a bit too much into the stereotype of a "dive bar." Some of the touring musicians I spoke with for the book also took exception to that subtitle, noting that the bathroom really wasn't or isn't that bad compared to that of other places they play--even in Chicago. When you're touring, they noted, a locking door and toilet paper can make a huge difference. The language from the awning Music Friendly Dancing always seemed to echo around my head. It felt more natural. It wasn't a big deal to change it.

You've played at the Bottle with which of your bands (all of 'em?), and during which eras?

I played in a punk band in high school and in a few DC bands that were short-lived and didn't tour, but otherwise I think any band I've played in for an extended period has played the Empty Bottle at least once.

In the nineties, I played with Chisel, a band we founded while studying at Notre Dame and eventually relocated to Washington, D.C. We played Chicago often, however, and recorded in Wicker Park. In surveying the club's old listings for the book, I was surprised how many times Chisel had played the Empty Bottle, how early on and with which bands. Some of the musicians that pop up in the book--Ken Vandermark, Brian Case, Jay Ryan were on those bills. In general, Chisel did our own booking and the Day-Runner was always kept updated with the number of whomever was booking the Empty Bottle at the time. While we played the Czar Bar, Fireside, Thurston's, Metro--we tended to play the Bottle. I think because they knew us and had been there from early on.

In the mid and late 2000s, I was with Perfect Panther (with former Reader scribe Miles Raymer), The Tax (a garage band from Athens, OH that had reconvened in Chicago) and Chicago Stone Lightning Band, all bands that played the Empty Bottle regularly. And a few years ago, I played drums with Zed or Zjed for a few Empty Bottle shows. Then booker Pete Toalson was always receptive to the bands I was working with--as well as forgiving. I've certainly had a few off nights there. Drum crimes and rhythm fouls.

How long did it take you to compile all the stories? When did you start hitting people up? And how many interviews did you do for the book?

The project started taking shape in late 2013--it was announced on Chicagoist around that time, I believe. I started reaching out and doing interviews in March 2014 and calls for submissions went out from the club and publisher. Material gathering didn't ramp up until a bit later--and took place sporadically. Between interviews, submissions, essays, there are approximately 116+ voices in the book.

What was the most surprising detail or indelible memory about the Empty Bottle you came out of this book project with?

I love detail, but this project, perhaps because of its sprawling nature, became about seeing things more broadly, almost taking an outsider's perspective to try and see what's special about this place, if anything. For a lot of folks, the Empty Bottle has been their living room. It's a place they grew up in, so they take it for granted in some ways. It's so obviously not perfect, but somehow it (usually) works. The consensus from our contributors was really that the booking--the "curation" if you will--has always been tremendous, that's the calling card.

It was exciting when someone could recall an unusual show like it had just happened the night before and I could picture it in my mind's eye. The Flaming Lips playing an encore on the beat-up piano, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs playing an opening set, Jay Reatard grabbing the disco ball, someone legendary like John Fahey, Terry Reid or Jandek playing there and someone interacting with them. It's all very personal, which I love.

I came away thinking a lot about memory and moments. If life is made up of moments, what makes us acquire some moments and not others? Why did we hold on to one from the Bottle? Some of the most indelible nights of our lives are spent in these places (The Black Cat, the Empty Bottle, etc.), so is there anything to it beyond cheap drinks and really loud music? We love music. What else is there? Community? It's odd to think that this is where we go searching for the sublime, but a lot of us do.

What was surprising in a way was just the overwhelming humanity of the place, the social network that revolves around it, the music culture that's built up in this part of town over the decades. I was also struck by how Chicago continues to reckon with the nineties--so much was set in motion in that era and we're still living with it in some ways. And how this music--what was once considered underground--is so closely connected to this city or how people see their lives here, why they're here. Hopefully, some of this comes across in the book.

This Heat, Charles Hayward

HBO's Vinyl for the Economist

So Vinyl is a bit of a mess, but there's something that keeps me watching hoping it will go somewhere. I wrote up the HBO series debut for the Economist Prospero blog.

Chris Stamey of the dB's on Ork Records | Interview

I emailed Chris Stamey with some (simple) questions about Ork Records and working with Alex Chilton for an Economist piece on the Numero Ork box. Here's the complete interview.

Hearing and seeing Television in 75 or 76, did you have an idea something new was happening? That this represented a new direction or not so much?

Much has been made of the way the band looked, the lack of shiny costumes and standard artifice, the lack of posing and rock-theatrics tropes. But the real--and very new--difference was obvious if you closed your eyes. They seemed to have sprung from a heritage that had lept over the blues and Chuck Berry, as if most of the 60s and 70s had not existed. It was an improvising quartet that touched both Albert Ayler/John Coltrane jazz and Midcentury Modern university music, with a freedom that was exhilerating and electric in the best sense of the word. I did connect it to a few rock things--the Hampton Grease Band live in the south, the Jeff Beck Yardbirds, a bit of the Who--but was riveted by the way the band sustained an attentive concentration. Listening, you had the sense that anything could happen at any moment, that danger was afoot, they were chasing down the molecules of time.

It's hard to say how that shock of the new happens. It's a flavor, difficult to describe. And rare. Like the judge said about pornography, " . . . but I know it when I see it." And there was no mistaking, from the first few notes, that Television was remarkable. They gave me hope.

A lot has been made of the whole CBGB scene, but I never heard any of the other bands that were remotely similar to Television.

And one clear difference--they rehearsed a lot! Extreme dedication there. They were a precision outfit when they needed to be, although keeping the guitars in tune without pedal tuners and guitar roadies made them seem less so. (There were no pedal tuners then, and no money for guitar techs, either, of course.)

One more thing: there was a sense that they were not lying to you the listener, and that they were trying to express difficult and perhaps important things in the same way that poetry does. It's hard to believe the degree to which most 70s rock was all about telling obvious lies to an enebriated audience, but I remember, I was there.

What was the NYC "scene" around Max's, etc. like for you? Inspiring or not so much?

Max's was a nice club to play, but a bit weighed down by the legacy of decadence, maybe the VU live record had changed expectations there. Anyway, CB's was my hang, not Max's so much. I could get in free at CB's but not at Max's!

What was your take on Ork Records at the time?

I was somewhat on the inside, as Charles Ball from Ork was managing Alex Chilton as well (I was in Chilton's band), and he liked to talk about what was going on. I thought it was total chaos, another inmates-take-over-asylum situation, but it was true that the major labels were everywhere and that Terry Ork himself was constantly enthusiastic no matter what. But there was no illusion that it was a functioning business, just phone calls from pay phones and scraps of paper in pockets with holes in them. The book that comes with the Numero release talks about heroin a lot, but this was hidden from me, it did not seem like a part of this. The atmosphere was one of change and excitement, and it seemed like there was a lot of good-will toward the label from the NY press and label folks, that they, too, were ready for a sea change.

How would describe Terry Ork? Why would anyone make a record with him in those days?

Here is my description of Terry, from the book that comes with the record: "Terry was a benevolent presence in the scene. He was our Jerry Garcia, a smile big as all indoors, with a halo of chaos and insurrection. He gave everyone hope and encouraged all efforts, however nascent and tentative, with dreams of world conquest."

Do you think the label captured the spirit of that era?

"Little Johnny Jewel" is a great record that was their first but also their greatest accomplishment. It was influential in some quarters the same as "seeing the Beatles on Ed Sullivan" had been years earlier. I am not sure that the label ever topped that one.

Is it accurate to call it the first punk 45 label?

This is a musicologist question, not one for me, what label were the 13 Floor Elevators on? The Seeds? It was probably the first American label to have such a strong French new cinema background.

Was the label influential? Important?

Every Ork record was paid attention to because it was Ork. Same as Stiff.

With the Cossacks, how functional was Alex Chilton? How did he fit into what was happening in NYC?

He was brilliant, very kind, witty/sardonic, and a very very good musician. He was a bit sad at times, getting over the end of a love affair. He gradually modified his approach to playing the clubs to fit the wildness of what was going on around him, both out of enthusiasm and also just a desire to be popular and draw bigger crowds (in my view).

PLEASE listen to this, as proof of his attitude, from a cassette at a rehearsal right before he and I played CBGBs for the first time:

He thought we were going to be taking over the world shortly! That was the spirit. Maybe you should give this as a hotlink in your article?

Many view this era in Chilton's career as a dark time, is that accurate?

He got worn down, later that year (1977), as he was dirt poor in NYC but with everyone buying him free drinks at the bars. But his playing in the later live gigs (not the Ocean Club record, which was the first gig after only 2-3 rehearsals) was fantastic, great guitar playing.

You had him produce your first solo single. How was working with him in the studio?

I learned a ton. It was a master class in making the technology serve the art, instead of the other way around. See the Ork book. Here is an excerpt from my annotated songbook (as yet unpublished), New York Songs:

"[H]e found the Beach Boys side of the song when he produced it for Ork later that month, with just the two of us playing all the instruments and singing all the parts, Alex turning compressor knobs until they cried for mercy, commanding that we “sing like hounds” on the backup “ah-oop”s. He arranged it on the spot so that every instrument had a purpose, his drumming hitting just the beats that were crucial, his concise guitar solo a marvel of economy in the thirds-harmony style of the Beatles’ “And Your Bird Can Sing” (the tune that was also the template for the rhythm guitar groove of his own classic “September Gurls”)."

Ork teased a Chris Stamey album as a follow-up to "Summer Sun," but this never happened. Why?

They were broke.

When Conny met the Duke...

I wrote about this somewhat hard-to-believe meeting between Duke Ellington and Conny Plank in 1970 for The Economist's Prospero blog. I spoke with Plank's son, Duke's son and Michael Rother for the piece. My conversation with Rother was longer than necessary and revealed a lot about the relationship between Plank and Krautrock musicians in general. When I have time, I'll edit that and post it here. In the meantime, you can find the piece on the Economist.com.

Red Red Meat - Bunny Gets Paid

Protein sheiks

A bluesy, woozy classic from Chicago’s indie heyday gets the royal treatment. By John Dugan

Bunny Gets Paid (Deluxe Edition) (Sub Pop)

In the mid-’90s, Chicago’s underground scene was hot

as shit, after Smashing Pumpkins and Liz Phair broke

through to radio. Still, revolutionary rock label Sub Pop

surprised many when it picked up local act Red Red

Meat’s second album, Jimmywine Majestic, in 1994.

On the surface, the Chicago-based quartet had

much in common with the grunge rock of the era: It

mined beloved collections of ’60s and ’70s albums for

raw riffage and cultivated an attitude equal parts

blasé, nihilistic and nostalgic. Guitars, fuzzed and

blurred, were the act’s forte. But Meat was too quirky

for the tag and for alt stardom—and it didn’t go in for

bare-chested amplifier stabbing. The band also,

perhaps unwittingly, built on Chicago’s electric

blues heritage.

Sub Pop, ever the tastemaker, has done well to

select Bunny Gets Paid for a timely rediscovery and

two-disc reissue with extensive artifacts from the era.

Thanks to Fleet Foxes, Grizzly Bear and their ilk,

atmospheric folk experimentation is in. Red Red Meat

defined that vibe on “Sad Cadillac,” a slow,

disorienting meditation, with the line “someone

pissed in the hibachi.” Fittingly, the first word on the

album centerpiece, “Gauze,” is medicated, and the

album continually conjures visions of Keith Richards

on a Robitussin binge. Bunny is a beautiful mess,

precisely rendered.

At times, Tim Rutili’s songs dance dangerously

close to a version of alt-pop exuberance, as he

communicates by primal tones rather than lyrics—

his mumbling codes so mysterious they could be

backward. But FM-worthy sing-alongs, such as

“Chain, Chain, Chain,” make it an approachable

record, too. The record majestically balances noise,

folk, rock, blues and a tune from the 1964 Rudolph the

Red-Nosed Reindeer Christmas special. The group

even toured with Smashing Pumpkins.

So why didn’t Bunny Gets Paid send Meat to starry

heights? Splitting in 1997, Rutili and other Meat men

carried on as Califone, while drummer Brian Deck

went on to produce acts like Modest Mouse and

Counting Crows. Perhaps the problem was that,

outside of Chicago, playing gigs in a seated position

often came off as a fuck-you rather than a humble

gesture. Today, bands can do gigs on a stool or, hell,

even curled up in a beanbag. It might not have hit the

buzz bin the first time around, but Red Red Meat was

really on to something.

Red Red Meat reunites at the Empty Bottle Tuesday

17 and Wednesday 18. See Listings. Bunny Gets Paid

(Deluxe Edition) is out now.

March 12–18, 2009 Time Out Chicago

Salad Days Interview

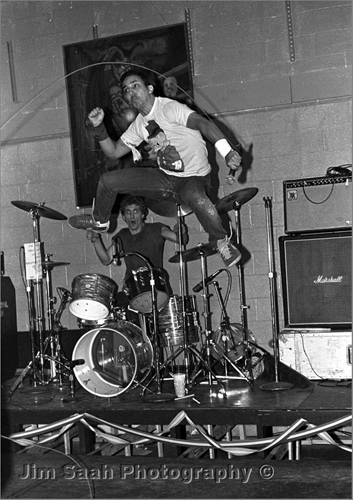

I chatted with writer/director Scott Crawford about the new DC '80s punk/hardcore doc Salad Days | A Decade of Punk in Washington,D.C. (1980-1990) for the Chicago Reader.

Having grown-up around the D.C. punk scene, I started soaking up the most important records, the local folk tales, the characters and as much inside info as I could from my pre-teen years into my show-going and show-playing years and especially when I was home from college in the late 80s, early 90s. I continued to pick up bits and pieces of the hardcore story well into my late twenties. From an early age, I regarded DCHC as important culture with an important cultural history. I'm not the student of DCHC I once was, but I still love to jaw about the great records and historic shows when given the chance.

Salad Days is a bit of a primer for the casual music fan or younger punks. It'll school you in the basic timeline, the major players and the major acts of the early-to-mid '80s in Washington, D.C.. I'm glad it's been made and I love seeing the footage of the bands and legendary shows which I was just too young or not quite in the loop to see.

MacKaye and Henry Rollins are magnetic in their comfort with the material and knack for storytelling, as usual. One wonders how long it is before their tales of punk life in Georgetown are officially American folklore. Some of the doc’s best moments occur when those not heard from as often (Sab Grey of Iron Cross, Michael Hampton of of SOA/Faith/One Last Wish/Manifesto, Mark Sullivan of Slinkees/King Face, Mark Haggerty of Iron Cross/Gray Matter) deliver pithy insights.

saladdaysdc.com

Someday soon, I'll get around to posting my own D.C. punk videos, filmed on my family Realistic camcorder, but until then you can get by with Sohrab's incredible archive, available on Vimeo.

Remembering David Carr

It's entirely possible that without David Carr, I wouldn't have done as much writing and editing as I have over the past twenty years. I landed a gig as a production artist and ad designer at the City Paper in the mid-nineties. I started writing music pieces, previews and reviews with the encouragement of the arts editor Glenn Dixon, but it was Carr as new editor-in-chief who made me feel as if I could do more than pay off my endless D.C. parking tickets by penning record reviews and band profiles. Taken with a long review of a new Sloan record that City Paper had published, he asked me about my craft, how I wrote, what my process was. You could say I was flattered. I sensed that he did that with a lot of writers out of curiosity and enormous appetite for journo shop talk, but also to help them realize what was particular about their process. Carr was a master of the compliment. He offered up his jealousy for anyone such as I who could play in a band and write well. That's the kind of compliment you keep in your pocket forever, just in case you need it.

Carr was a passionate fan of music, too. I liked to drink in his stories of wild times with the Replacements, Soul Asylum and Husker Du during his Minneapolis days.

He was also gracious in hearing criticism. I once met with him in his office to vent about some oddly nasty takedown pieces CP had published on local musicians. He respected my point of view as someone with friends in music, but defended the stories on the grounds that he liked the writer's voice. He was a writer's editor.

Carr liked the idea of connecting people that might otherwise never cross paths. He invited me to start joining City Paper editorial meetings. Now, I wish I had attended more. He took me along for outings with writers, journalists and politicos. Once, after an AAN convention event, he somehow got a bunch of us into the Tibetan Freedom Concert after show at the 9:30 Club. Another night, he popped into the production room and introduced the staff to his buddy the comedian Tom Arnold who was sporting a George Hamilton-esque "I'm from Hollywood" glow.

When closing the issue on Wednesday nights, the editor was supposed to flip through the layout pages to be sent to the printer and sign off on them. In a loose CP tradition, the cover story writer brought in beer for the remaining edit staff, production artists and took a final look at their story. At some point, Carr got in the habit of asking me to sign off on the pages instead, which was interesting as I was drinking and he wasn't. It gave him a chance to visit with his family or jaw with the writer, but it also was like the captain standing on the deck saying Go ahead and take the wheel, this paper is as much yours as mine. David Carr treated a lot of us like first mates and that's something we'll never forget.

Cerrone for Time Out

Rory Phillips recently posted a Guardian article about Cerrone, so I dug this out to share.

Thirty, but still flirty

It’s time to give Cerrone’s disco originals another spin. By John Dugan

The music of disco pioneer Giorgio Moroder has gotten a thorough reappraisal in recent years, but another influential producer, France’s Cerrone (Jean-Marc Cerrone), has been a bit neglected. Which is strange, because Cerrone is far from obscure: He sold more than 3 million copies worldwide of his raunchy 1976 debut, Love in C Minor, and DJs and artists of many stripes still hold his penultimate album, Cerrone 3, in high regard. You’ve probably heard more Cerrone than you think: His recordings are heavily sampled by everyone from Daft Punk to Lionel Richie. On the 30th anniversary of his breakout year, five albums by Cerrone get the royal treatment with CD reissues and a vinyl box set on the Malligator/Recall label. Also this month on Recall, Cerrone by Bob Sinclar—a 2001 million-seller mix-CD—finally reaches the States.

We recently gave Cerrone a ring while the drummer, composer and singer was passing through New York. When not touring, he’s planning a huge dance party for next October in New York’s Central Park (www.nydanceparty.net) featuring his and Nile Rodgers’s bands playing live to 70,000 dancing people. He hints that he may bring the Chic/Cerrone tour to Chicago sometime thereafter—all part of his efforts to make dance music a live experience. “That’s why I do this business: to play, not to be an engineer or a DJ and play the music of someone else,” Cerrone says in a thick accent. “The emotion come[s] from the body and specifically the drummer.”

“I don’t make music for radio, I make it

for myself and the discotheque.”

His music career started one Christmas, when the fidgety 12-year-old Parisian got a real drum kit from his mother. As a teen, he convinced Gilbert Trigano, the devout communist who ran Club Med, to hire him to put together bands to play at the resorts. For four and a half years, Cerrone booked some 40 funky rock bands at the Club Med “villages” in Italy, Spain and elsewhere. It was a big learning experience, evidently. “It was also the beginning of a sex life, because trust me, at the beginning of Club Med, that was really something,” he remembers. “A lot of people ask me questions about [Studio] 54 and how fun that was. Trust me, the Club Med was stronger. You can’t imagine.” His band the Kongas held residency at St. Tropez and penetrated ’70s New York with “Anikana-O.” Cerrone picked the best bassists and keyboard circuit for himself.

When he recorded a 16-minute song for his first LP, it was designed for a purpose the biz had yet to envision. “If you go back to that time, all major companies, all radio look at me like a strange guy coming in from the moon. And everybody said to me, ‘How can we play 16 minutes on the radio?’ My answer was always, ‘I don’t make the music for the radio, I make it for myself and then for the discotheque.’” Moroder had hit gold a few months earlier with Donna Summer, and Cerrone’s debut joined disco’s first wave of smashes in ’76.

In August of ’77, Cerrone unpacked his first synth. “We started to find a few sounds that were so strange. So I play the drums with the synthesizer live.” The result, “Supernature,” is a disco landmark, and a punk one. Friend Lene Lovich contributed sci-fi–inspired lyrics for Cerrone 3 and loads of other Cerrone releases.

The reissues sport the original scandalous album art—think a naked woman on top of a refrigerator. “At that time, about ’75, [we got] the pills for the girls not to get the baby,” he says. “You don’t imagine what kind of a revolution [it was]. So when you produce music for the discotheque, you try to find sex. It was logic to get a girl on the front of the sleeve.”

It’s also logical that he makes a nice euro from sample publishing. “I don’t think it’s bad for me to ask for so much,” he says. “That kind of music needs a real atmosphere, otherwise you’ve fucked up.”

Cerrone by Bob Sinclar and CD reissues of Cerrone’s first five albums are out Tuesday 14 on Recall Records.

November 9, 2006